Encouraged by a great teacher of religion and philosophy, I spent much of my high school and college years surfing the internet (before the time of Google and Wikipedia) to learn about a variety of philosophical and religious traditions. Having eschewed the stuffy Judaism of my youth, I found myself developing a practice of Buddhist meditation and yoga asana – and looking for more vibrant, mystical and meaningful versions of my ancestral tradition.

By the time I lived in Berkeley for a year in my late 20’s, I was doing 5:40am zazen at the Zen Center, training to become a yoga teacher, had taken the shahada to become Muslim at a mosque in Oakland, and found a really cool synagogue identified with the Renewal movement (as well as happenstancially working at a Jewish deli!). One of my favorite days of that time period was a Friday when, having the day off from the deli, I got in a morning yoga class, ju’uma at the masjid, a dusk “sit”, and ended the day with nonstop ecstatic dance at a Shabbat service after the sun went down – all within walking distance from where I lived!

My collection of religious identities and practices might be characterized by what Jorge Ferrer called spiritual individuation, “the process through which a person gradually develops and embodies her or his unique spiritual identity and wholeness”. Ferrer writes in his book Participation and the Mystery (and an abridged version as an essay in Tikkun magazine) about a “participatory pluralism” which “allows the conception of a multiplicity of not only spiritual paths, but also spiritual liberations, worlds, and even ultimates”. He also illustrates that a participatory approach to spirituality must be embodied, integral, and relational.

As I have explored religious practices in my search for spiritual individuation, one of the challenges of an embodied and integral participatory orientation has been how to navigate the areas where the various traditions differ. For instance, do I imbibe when Judaism asks me to although Islam (and, generally, Buddhism) prohibits it; and do I eat shellfish because Islam allows it even though it’s treyf in Judaism (they both abhor pork, so I, too, avoid it!)? My practice and understanding of these various traditions is that of a humble casual student; I do not claim any expertise or perfection, yet I regularly seek to deepen both.

Last spring presented an interesting opportunity for embodied spiritual inquiry when a number of religious occurrences collided – and I had to newly discover the best way to incorporate them into the dynamic flux of my life. The Jewish holiday of Purim fell on the same day as St. Patrick’s Day; and Passover overlapped with Ramadan! Sensing an immersive opportunity, I dove in headfirst!

While I don’t identify as Irish or Catholic, St. Patrick’s Day has become an American holiday in this multicultural society and its spirit – to eat, drink, and be merry – seemed to be a good enough reason to partake. So, at the risk of conforming to cultural appropriation, I thought I’d dabble in Dublin the fun!

Purim happens to have a similar ethos. The holiday centers around one of Judaism’s most famous melodramas: Haman, an evil man who is the advisor to Persia’s King Ahasuerus, plots a genocide against the Jewish people. A Jewish man named Mordechai learns of this plot and implores his niece Esther – the heroine of the story and one of the king’s wives – to ask the King not to follow through with this plan. Ultimately, the Jews prevail. And, like many Jewish holidays, we celebrate the continuation of our peoplehood with food, drink, and liturgy!

The official mitzvot (“commandments”) of the Purim holiday include hearing the aforementioned Purim story, or Megillat Esther, often along with a purimspiel play; hosting a Seudah (feast); and giving both mishloach manot, gifts to friends, and matanot levyonim, gifts to the needy. Over the years, it has entailed costume parties, parades, and carnivals – and substantial merrymaking within Jewish communities. More generally, Purim is thought to be the most licentious Jewish holiday, fulfilled by getting so shicker that you can’t tell the difference between Haman and Mordechai – villain and hero.

In the West, Jewish holidays occur on slightly different dates every year, due to the misalignment between the Hebrew calendar and the Gregorian calendar. So it was quite the synchronicity that Purim and St. Patrick’s Day both fell on March 17 in 2022. According to the Jerusalem Post, this is the first time the holidays intersected in almost 40 years. The article also notes that “despite the fact that they come from vastly different backgrounds, the one thing both holidays have in common is the tradition of revelry and booze.”

[Also worth a look is another article from the Jerusalem Post which highlights the last time the holidays intersected in 1984 – and an ensuing episode of Saturday Night Live lampooning the “stereotypes of these two holidays, alongside the happy calendrical coincidence”.]

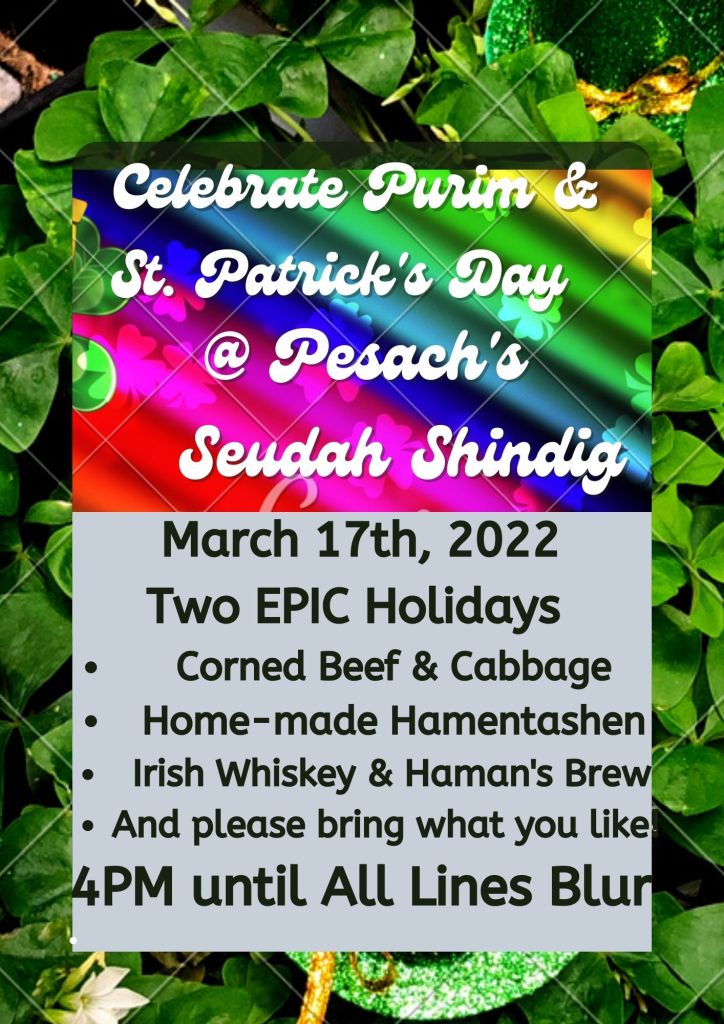

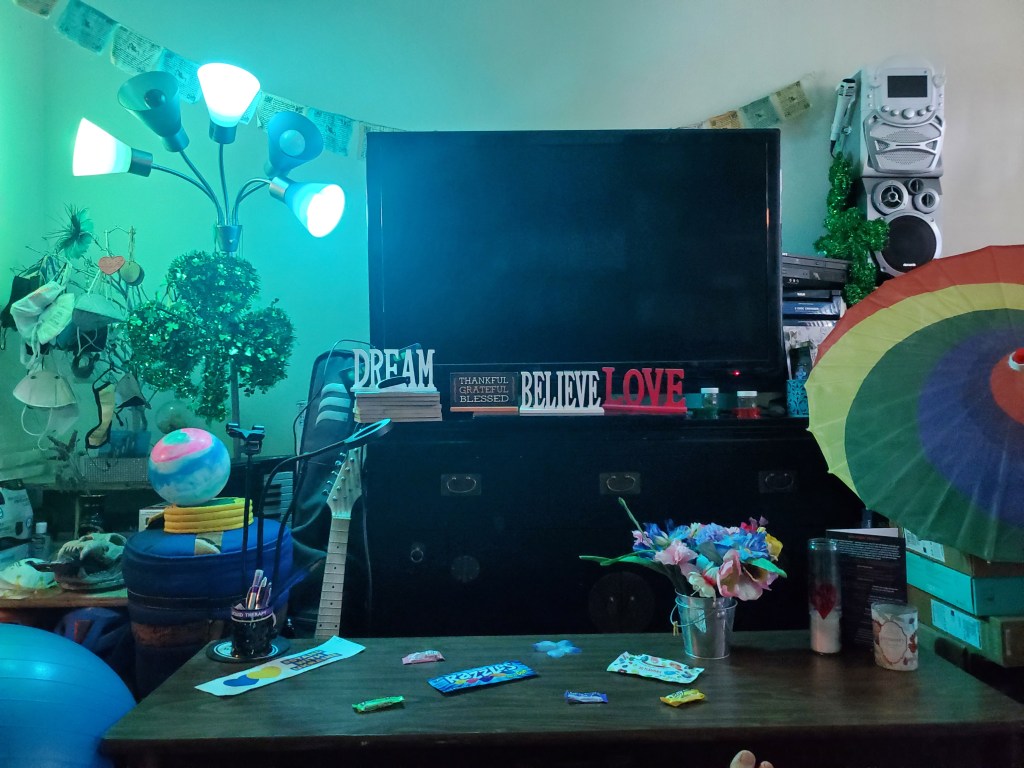

Following the call of a participatory approach to religious observance, I decided to throw a feast in honor of both Purim and St. Patty’s Day. I prepared 30 home-made hamentashen, a crock-pot of corned beef and cabbage, and a variety of libations. In the spirit of also observing a Jerusalem or Shushan Purim, I continued celebrating for another few days. I decorated my living room in the spirit of the festivities, all while simultaneously packing for an interstate move just two weeks away! I wanted to see our friends before we left, so I sent this “seudah shindig” flyer to about 40 people:

Taking a closer look at the rhythm of religious observance, it is interesting to note Purim’s similarity to another debaucherous spring celebration – Mardi Gras. Rabbi Polish wrote that

“both of these celebrations are marked by a raucous atmosphere, the excessive consumption of intoxicants, masks and costumes and the transgression of even the most consequential social norms,” with both holidays serving as “the last eruption of self-indulgence before the prolonged period of self-denial leading up” to Passover and Easter, exactly one month later.

Just like Purim, St. Patrick’s Day, and Mardi Gras seem to be life-affirming celebrations of a verdant Spring, the confluence of Passover and Lent/Easter appear to emphasize spiritual discipline and maybe even austerity. When Passover came in mid-April, I abstained from chametz for 8 days. Now, chametz is generally translated as leavened bread. The ritual descends from the Exodus story that the holiday is based on, when our ancestors needed to flee the authoritarian and homicidal Pharoah in Egypt and didn’t have time to let their bread rise.

By the time Passover started, however, I was already halfway through Ramadan, which began on the Gregorian April 2. Because the Islamic calendar follows the moon’s revolution around the Earth, its holidays will cycle throughout the year, occurring approximately 10 days earlier every year. Both the Gregorian solar calendar and the Hebrew lunisolar calendar include leap years which prevent this phenomenon – so, although Jewish holidays fluctuate a few weeks every year, they always occur within the same season. Ramadan, however, will occur throughout the seasons if one zooms out enough decades.

The observance of Ramadan is practiced during the month of Ramadan, the 9th month of the year. Ramadan almost feels like spiritual boot camp: priority toward praying, often in community, and allowing the space for Allah that would normally be occupied by our nefs (primal instincts). During this period, no food or drink is to be consumed after the fajr prayer or before the maghrib prayer, the times of which fluctuate througouth the year, but this year were about 4:30am and 7:30pm. So, for one month, I abstained (mostly) from eating and drinking for nearly 15 hours each day. Sex is also prohibited during these times.

The word Ramadan derives from the Arabic root R-M-Ḍ (ر-م-ض) “scorching heat”, which is the Classical Arabic verb “ramiḍa (رَمِضَ)” meaning “to become intensely hot – become burning; become scorching; be blazing; be glowing”. The Hebrew word for the holiday Passover, חַג הַפֶּסַח, also has connotations of a sacrificial offering – so, between the two holidays, I had a lot at stake. I had already been abstaining from food generally from sunrise to sundown for a month, with 8 days in the middle requiring an additional foregoing of chametz when I did eat. I also had the fun challenge of needing to balance participating in the Passover seder with my family with stepping away for a few minutes to conduct the salat prayer at the time specified.

Passover is ultimately about liberation. And you can imagine the immense sense of freedom that comes when it’s over and you can, once again, eat whatever you like. But this is ironic; it is actually Passover itself which is meant to symbolize liberation. Although there are plenty of possible ways to explain the liberation of restricting one’s practices, I would argue that simplifying one’s choices opens up more space for spiritual adherence.

Ramadan has a very similar effect. I enjoyed not having to cook many meals for myself, simplifying my life and allowing more time for the 5 daily prayers. And then, when I finally had that glass of water or gluttonous (but not glutenous during Passover!) iftar feast, I was so filled with gratitude. And at the end of Ramadan, commemorated by the holiday Eid al-Fitr, I treated myself to breakfast at a fancy downtown cafe – my first breakfast in a month! Mindfulness around our consumption, which might increase our mindfulness more generally, inspires gratitude for what we do have.

I’ll end on a sober note, writing this after a full year of reflection since the observances described. Through embracing multiple religious traditions, I do so with reverence for the spirit of the law for each, rather than any orthodox attachment to the letter of the law. Although I celebrated Purim/St. Patrick’s Day with alcohol, intoxicants are very seriously prohibited in Islam. I took liberties with my adherence to the religion throughout the year, but during Ramadan had no alcohol, using grape juice instead for the four cups of wine required during the Passover seder.

In the last year, however, I decided that the prohibition of intoxicants in both Islam and Buddhism dwarfs the custom of drinking in Judaism (and general American culture), so both my Purim and my St. Patrick’s Day – this year 10 days apart – were dry. I still attended a purimspiel and made corned beef and cabbage, and honestly didn’t miss the libations one bit. Once again, however, Passover took place halfway into Ramadan (which both fell a week or so earlier than last year).

As this hadn’t happened for some time prior to last year and won’t happen again for many more years, I was excited to get one more shot at benefitting from the overlapping opportunities for spiritual discipline and liberation. Whereas last year I approached the confluence of holidays with a sense of awe and mystery for the divine timing (and in the middle of a big move), this year my experience was pretty uneventful. Rather than astronomical, the holidays were grounding. I’m reminded that, as we spiral once again through the same holiday cycles, we never know how they might affect us – the world is different than it was the year before, I am different.